How can using psychological theories of persuasion make safety campaigns more effective?

Efforts to improve safety through communicating the risks publicly have been made for well over a century, with organizations such as RoSPA being established in 1916 and the UK government running road safety campaigns for more than 75 years.

All safety campaigns seek to persuade people to adopt different behaviors to keep them and others from harm. Over recent years many communications practitioners have turned to psychological theories of persuasion to achieve this aim. So, what can these theories teach us about making safety messages more effective?

Methods of Processing

The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion (ELM), developed by Richard E. Petty and John Cacioppo in the 1980s, outlines two main ‘routes’ by which communications affect thought processes: central and peripheral. The employment of either the central or peripheral route depends on individual and situational factors, with the central route favored when there’s a high probability of ‘elaboration’ (deep thinking about a message), and the peripheral route favored when the likelihood is low (Cacioppo and Petty, 1986).

By contrast, peripheral processing uses simple, superficial decision-making based on cues such as physical appeal or the perceived credibility of the source and it happens when the person receiving the message has less motivation or ability to process it. They use quick ‘shortcuts’ that reduce the need to think more deeply.

The ELM suggests that while certain people may adopt safer behavior through listening to rational arguments, a large proportion may find such information irrelevant to them and are more likely to be persuaded by mental cues to make decisions, especially in our age of information overload.

It also emphasizes the need to look at what truly motivates the audience that the campaign is trying to target. For instance, one of the Health and Safety Executive’s most well-known campaigns of recent years was the Make the Promise, Come Home Safe initiative, which aimed to reduce the number of deaths and injuries in agriculture. The award-winning campaign encouraged farmers to pledge to return home safely for their families and was lauded for turning “a hard-to-articulate issue into something human”. It did this by focusing on something personal that would motivate many in an industry often built on family businesses.

The Fear Factor

Many safety campaigns attempt to use shock and fear to prompt people to change their behavior. Yet research on road safety education by Dr Elizabeth Box of the RAC Foundation found that this approach can actually be counter-productive, especially among young males, prompting defensive or even hostile reactions. How fear affects behavior has long been a contentious issue. The Extended Parallel Process Model, developed by Kim Witte in the 1990s, aimed to consolidate the theories previously developed. As with the ELM, Witte argues that there are two ways a fear-arousing message can be interpreted by the brain: Danger control and fear control.

Taking Shortcuts

American psychologist Dr Robert B. Cialdini’s 1984 book Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion builds on the idea of peripheral processing where people use mental shortcuts and argues that “the ever-accelerating pace and information crush of modern life will make this particular form of unthinking compliance more and more prevalent in the future” (Cialdini, Influence: Science and Practice, 2001: ix).

Cialdini says that influence is based on six key principles – he later added a seventh:

- Reciprocity: When someone is given something, they feel obliged to give something back.

- Scarcity: Individuals desire greater quantities of items that are scarce.

- Authority: Individuals tend to follow the guidance of reputable and knowledgeable authorities.

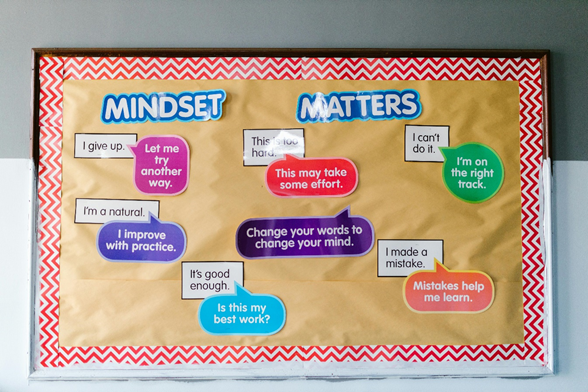

- Consistency: Individuals tend to prefer maintaining consistency with their prior statements or actions.

- Liking: A person is more likely to agree with someone they like – and tend to like those who are similar to themselves, pay them compliments, and/or cooperate with them.

- Social proof: People look to the behaviors of others to determine their own, especially when they are uncertain.

- Unity: People tend to agree with those who share a membership in a category that is related to their personal or social identity.

The Rise of Nudge

- Easy: The BIT recommends that communicators should present their key message early, keep language simple, be specific about recommended actions, and break down a complex goal into simpler, easier steps to make it seem more achievable.

- An example of this can be seen in National Highways’ recent campaign, which is entitled Little Changes, Change Every Trade Documenting, and sets out a list of small changes that drivers can make that will help avoid collisions and make journeys safer.

- Attractive: This draws strongly on the ELM, advising that campaign developers should attract attention, either through a cognitive approach that finds new ways of highlighting the consequences of the behavior or through less direct feelings and associations. These should be personalized and draw on the need to have a positive self-image. Messages can also be made more attractive by ‘gamifying’ them.

- Social: This draws on the assumption that the majority of people want to conform to the ‘social norm’ by behaving as others do but warns against inadvertently reinforcing a negative social norm by making it seem as if a ‘problem behavior’ is actually widespread.

- Timely: The Behavioural Insights Team argues that timing is an often overlooked but crucial aspect of planning messages and advises planners to prompt people when they are likely to be most receptive and emphasize immediate costs and benefits, which are much more influential on people than longer-term results that can seem vague and hypothetical. It also espouses helping people plan their response to events in advance.

However, while encouraging the use of the EAST framework, the Behavioural Insights Team strongly advocates rigorous testing and trialing of new interventions, ideally through randomized controlled trials based on a thorough understanding of the context, warning that “changing people’s intentions, beliefs, or attitudes… will often shape our behaviors, but not necessarily directly and in ways that we might expect”.